A few weeks ago, I went out onto my back balcony, which had finally been liberated from the builders who had been redoing the siding, roof, railings, etc., of my condo for the last 4 months. I have a storage unit out back and I wanted to get a couple of things out of it. Right when I stepped outdoors, a robin started chattering furiously at me from the tree, and hovered around on the branches of the pine tree in front of my balcony, all the while scolding me. It took me awhile but I finally remembered that the year before, the same thing had happened and it was because a pair of robins had built a nest on the waterspout by the balcony. I looked over behind me and lo and behold, there was a robin's nest on the water spout full of little baby birds. They had returned to nest in the same place as last year. This really surprised me since the building had been undergoing massive renovation for months and in particular, recently the builders had been repainting and making all sorts of racket outside. But there they all were and I saw that the painters had only painted halfway up the spout in deference to the birds' nest, which was sweet of them.

A few weeks ago, I went out onto my back balcony, which had finally been liberated from the builders who had been redoing the siding, roof, railings, etc., of my condo for the last 4 months. I have a storage unit out back and I wanted to get a couple of things out of it. Right when I stepped outdoors, a robin started chattering furiously at me from the tree, and hovered around on the branches of the pine tree in front of my balcony, all the while scolding me. It took me awhile but I finally remembered that the year before, the same thing had happened and it was because a pair of robins had built a nest on the waterspout by the balcony. I looked over behind me and lo and behold, there was a robin's nest on the water spout full of little baby birds. They had returned to nest in the same place as last year. This really surprised me since the building had been undergoing massive renovation for months and in particular, recently the builders had been repainting and making all sorts of racket outside. But there they all were and I saw that the painters had only painted halfway up the spout in deference to the birds' nest, which was sweet of them.This got me thinking about the whole instinct that all animals seem to have to return to the familiar, especially as I had recently applied to renew my Taiwanese passport after over 30 years of not having one. My father and I are returning to Asia this fall. I say return because we are heading to Taiwan, my birthplace, and then China, his birthplace, to visit the old, probably not-so-familiar-anymore sights and to see former friends and even family who are still there. In the process, my father had decided to re-apply for a Taiwanese passport although we'd been US citizens for over 30 years. Partly this was because Taiwanese citizens can obtain a special visa to enter China and by so doing, we would be able to bypass having to get one as American citizens. When I had lived and worked in Taiwan about ten years ago, I had considered re-applying for my passport then but got stymied by all the bureaucracy in a language that I didn't speak or read very well, so I had forgone doing so. However, this time around, since my dad was already doing one for himself, I asked him to help me get one, too.

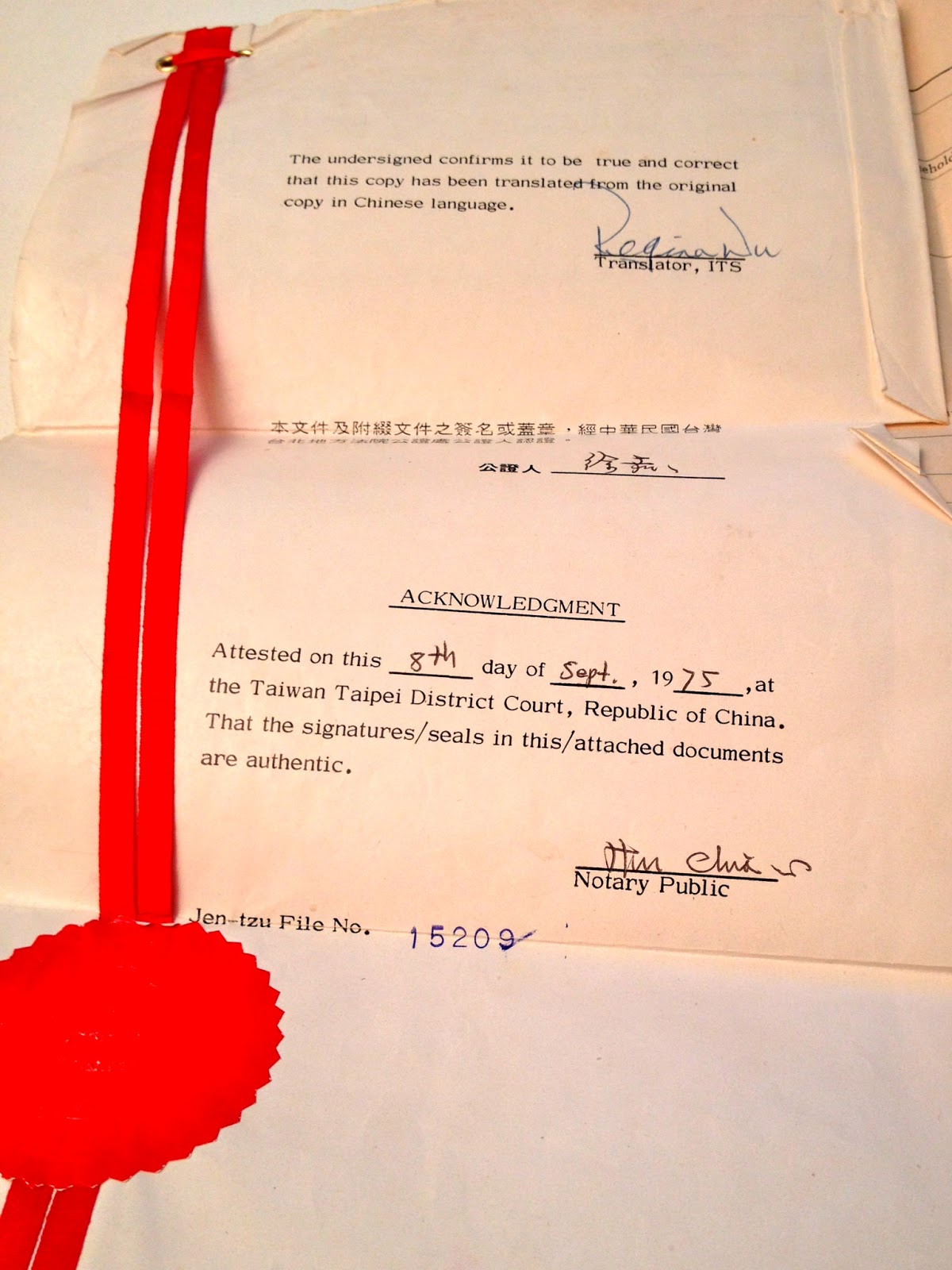

The process of applying for a Taiwan passport is much like any other: there are forms to fill out, passport size photos to be taken, and verifications of identity and residence. In order to show previous residence, my father pulled out what seemed like an ancient manuscript to me: a yellowing typed document with red ribbons dated from 1975. It was a notarized copy of our household registry, or hukou, from that time.

In Taiwan as well as China, Japan, Vietnam, and even several European countries like Germany, the household registry is an important document that tracks important family events like births, marriages, deaths, and immigration status. This process of recording dates back to the Xia Dynasty (2100-1600 BCE) when a system was needed in order to tax (what else), conscript, and keep track of the citizenry. In recent history, the method of hukou in China has been somewhat controversial as it has been used as a means to control the movement of rural citizens to urban areas where oftentimes more job opportunities are available. If a person doesn't have a legal hukou in the city, he or she can be denied employer-provided housing, health care, and access to other services, effectively becoming an undocumented worker in his or her own country. Before my parents had immigrated from Taiwan, they had the forethought to get their houkou translated and notarized and now, all these years later, it was needed again.

I had never seen or even known of this document's existence. Looking at it was truly like stepping into a time capsule. Seeing my grandparents' names in English [aren't all grandparents just called "kung kung" (grandpa) or "po po" (grandma)??] as well as my mom and dad and all my mom's various siblings' names really brought home the fact that despite not being very close to my relatives, that here was a document that inextricably tied us all together.

Ever the pragmatist, my father was not nearly so impressed by these papers. He filled out the paperwork for me (he reads Chinese whereas I barely do) and then one Thursday in May, he took the bus downtown to the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office (TECO) to get the forms processed. I wasn't able to accompany him as I had to work but from what he told me, usually the person who was filing the paperwork needed to be present to get the form processed. However, as a long-standing member of the Chinese community, he knew several of the people who worked at the TECO office and one of the administrative assistants, upon recognizing him, vouched for my existence and he was able to get the deed done. These are certainly times when having guanxi, or connections, is beneficial.

Probably not more than two weeks later, my father handed me my Taiwanese passport. Despite not really knowing the purpose of having one, it was still a thrill to get this newly minted passport that showed my birthright as someone born in Taiwan. My original Taiwanese passport had been issued when we immigrated from there when I was six years old. At that time, I didn't even have my own passport but instead, shared one with my mother. I still remember the black and white photo of me sitting with her from the passport although the passport itself had been long lost. On the back page of this new passport, there was a note that indicated just that exact situation: that I had originally had a passport with my mother, its issue date, number, and the fact that it had been lost. It seemed somewhat surreal that after all these decades, and what had seemed overwhelmingly difficult when I lived in Taiwan, was now accomplished so easily and quickly.

I read somewhere that robins will continue to go back and nest in the same spot year after year even if you try to discourage them by tearing down their nest before it's finished and that they also have an innate ability to know how to build the nest. I don't think that the desire by my father and I to return to the place of our birth is quite so evolutionarily instilled but who knows? Perhaps we're not as wise or complex as we think.

I thought I'd end with Li-Young Lee's poem "The Gift," which certainly is about legacy, planted in the narrator as a child, a gift that he only realized years later.

The Gift

by Li-Young Lee

To pull the metal splinter from my palm

my father recited a story in a low voice.

I watched his lovely face and not the blade.

Before the story ended, he’d removed

the iron sliver I thought I’d die from.

I can’t remember the tale,

but hear his voice still, a well

of dark water, a prayer.

And I recall his hands,

two measures of tenderness

he laid against my face,

the flames of discipline

he raised above my head.

Had you entered that afternoon

you would have thought you saw a man

planting something in a boy’s palm,

a silver tear, a tiny flame.

Had you followed that boy

you would have arrived here,

where I bend over my wife’s right hand.

Look how I shave her thumbnail down

so carefully she feels no pain.

Watch as I lift the splinter out.

I was seven when my father

took my hand like this,

and I did not hold that shard

between my fingers and think,

Metal that will bury me,

christen it Little Assassin,

Ore Going Deep for My Heart.

And I did not lift up my wound and cry,

Death visited here!

I did what a child does

when he’s given something to keep.

I kissed my father.

|

| Li-Young Lee, "The Gift" from Rose. Copyright © 1986 |

Have a nice day.

ReplyDelete